How Many Studies Does It Take to Change a Lightbulb – Part 3 – Some Roads are Shinier than Others

May 17, 2024

By Noah Sabatier

Part 3 of “How Many Studies Does It Take to Change a Lightbulb” emphasizes the often-overlooked impact of weather and the spectral reflectance of surfaces on lighting selection, highlighting the importance of considering these factors for optimal lighting design, particularly in outdoor environments.

If you have made it to part 3 of this article series, congratulations! You have now considered more evidence on real-world visual performance than those who decided to install white LED streetlights in your community. If you haven’t, please take a moment to catch up on Part 1 and Part 2 at their respective links. Today we will examine two more factors in lighting selection. Weather and the spectral reflectance of surfaces pose often-overlooked challenges to identifying ideal lighting designs.

In the first part, we learned the importance of visual adaptation to light. Visual adaptation relies on the luminance of the environment, something that varies with conditions. The luminance of any surface is based on its spectral reflectance properties. When a solid surface is illuminated, some of that light is absorbed while the rest is reflected. Not only do these reflectance values depend on the surface material, but they also vary with the wavelength(s) of light.

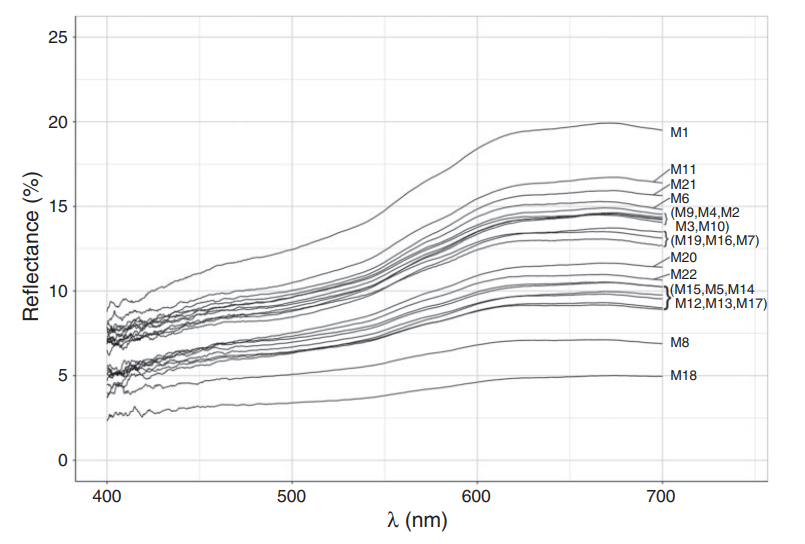

Spectral reflectance values are important for understanding two factors of lighting quality that often get left out of lighting guidance. Pavement surfaces such as roadways, parking lots and footpaths have a spectral reflectance that increases with wavelength. This means that, as the wavelength of light increases, more of the light is reflected to produce useful luminance. For example, on an asphalt test surface, 5.38% of light at 450 nanometer (nm) (ie. blue) is reflected. For 580 nm light (yellow), this reflectance value increases to 7.71%. When illuminating a paved outdoor area, less light is needed to produce the same pavement luminance when longer spectrums such as yellow are used.

A much greater difference in spectral reflectance is seen in regions that experience snowy winters. Pavement samples generally offer a spectral reflectance of 5-15% based on material properties and light wavelength. In comparison, the spectral reflectance of fresh snow is generally upwards of 95%. Ice has a lower reflectance of anywhere between 2% and 60+%. These values are deceptively low however, as the mirror-like surfaces often formed by ice produce specular reflections. Rather than light being reflected in a diffuse manner, specular reflection sends light in a single direction. Specular reflection is responsible for seeing an inverted ‘image’ of a light source in a puddle or patch of ice. This image-like reflection results in a luminance hot spot, similar to viewing the light source directly.

The image above shows 3 photographs taken at identical exposure settings in the same location. The photographs have been converted into a scale of relative pixel luminance. The left photo shows regular, dry road conditions. The center photo is taken shortly after rainfall and the right photo shows compacted snow, taken days after a blizzard. The wet road shows a great deal of specular reflectance, resulting in a higher luminance contrast on the surface. Certain regions, such as the puddle, reflect a luminance value close to the light source itself. The winter scene shows greatly increased luminance not only on the road but also on lawns, rooftops and the sky.

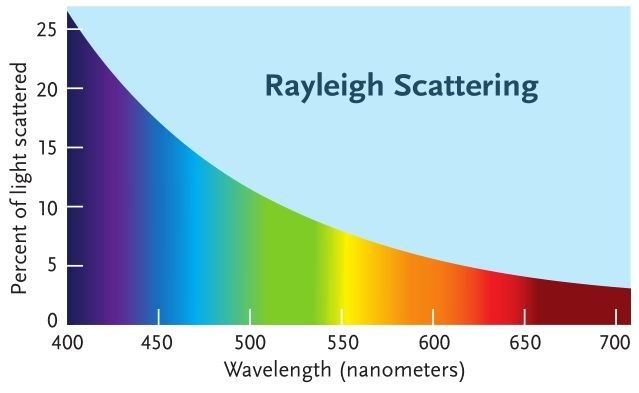

A more universal issue for outdoor lighting is that of atmospheric moisture. Water particles fall under Rayleigh scattering, a physics principle that applies to particles smaller than the wavelength of light. The percentage of light affected by Rayleigh scattering is dependent on wavelength, with shorter wavelengths being scattered at higher rates. This can often be seen in foggy conditions and is the reason that fog lights are generally yellow, a relatively long wavelength of visible light. Regions subject to fog will become more hazardous if the wrong spectrum of light is used.

Interactions between light and the environment play a crucial role in implementing quality lighting. Lighting designers must pay attention to the spectral reflectance of the surfaces they’re illuminating, especially if they are using illuminance rather than luminance.

Since illuminance is merely a measure of light landing on a surface, it does not account for varying levels of reflectance. This can cause differences in pavement luminance for different spectrums of light, even if lux levels are the same. It is also important for designers to consider local weather patterns in their region. Surfaces subject to regular rain will experience higher levels of luminance contrast while snowy regions will see an overall increase to luminance levels.

Noah Sabatier is a photographer and lighting researcher that is dedicated to advocating for better outdoor lighting. Noah has spent the past 5 years living with a night shift sleep schedule, during this time he realized that the streetlights in his city were far from optimal – and recent changes had only made them worse. He has spent the past 2 years extensively reviewing scientific literature and technical documents alongside others advocating for better lighting. Noah is now working to raise awareness of common misconceptions that lead to bad lighting and the better practices needed to solve this problem.

Reach him at: noahsabatierphoto@gmail.com

Works Cited

Preciado O, Manzano E. Spectral characteristics of road surfaces and eye transmittance: Effects on energy efficiency of road lighting at mesopic levels. Lighting Research & Technology. 2018;50(6):842-861. doi:10.1177/1477153517718227

John Hopkins University Spectral Reflectance Library

Lichtverschmutzung messen & Messgeräte zur Messung/Einschätzung (paten-der-nacht.de)

https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-resources/transparency-and-atmospheric-extinction

A. J. Cox, Alan J. DeWeerd, and Jennifer Linden, “An experiment to measure Mie and Rayleigh total scattering cross sections”, American Journal of Physics 70, 620-625 (2002) https://aapt.scitation.org/doi/10.1119/1.1466815

Related Articles

Part 1: How Many Studies Does it Take to Change a Lightbulb?